Introduction

According to Anna-Leena Siikala, various

scholars have concluded that “shamanism is the oldest cultural legacy of

Finnishness”. She

relates Martti Haavio’s view that Finns, Suomalaiset, are heir to “an

ancient shamanistic institution” that “drew upon the shamanistic practices of

northern Eurasia”.

|

| © Johannes Setälä, from JUM, 2018 www.salakirjat.net |

In the present series of posts, A History of Finnish Shamanism, I am exploring the roots of this millenniums-old Uralic-Finnic shamanic institution, particularly its presence in Finland and Karelia. With ancestors, I call it ‘the great shadow tradition’, existing alongside the other great shamanic institution, the Arctic-Saami, which I have explored in earlier posts and will revisit in coming posts.

I am focussing here

on prehistoric sacred art, that provides a unique window on the Uralic-Finnic

shamanistic tradition. Clottes says that

within the context of shamanism, “art could be a privileged means of entering

into a relationship with the spirits of the supernatural world and of retaining

the powers that this contact made it possible to obtain”.

In the present post, Part 3, I explore what I consider to be a new sacred art tradition that began in the Middle Urals in the early Mesolithic, that I call ‘three worlds naturalism’. In subsequent posts I will explore the initial formation in the Mesolithic of the Uralic-Finnic shamanic complex that carried the new tradition across the Northeast European forest zone and look at artworks rendered in the tradition, particularly those from Finland and Karelia. Subsequently I will follow the sacred art tradition into the Neolithic Era, particularly as it influenced the rock carvings of Lake Onega in Karelia and the rock paintings of Finland.

|

| An imagined Neolithic shamanic performance by a member of an archaeological team at the site of rock carvings, Lake Onega, Karelia |

To honour the wish of ancestors, I am attempting to recount this story from the viewpoint of the Uralic-Finnic shamanists of prehistory themselves, accepting with them the reality of the three cosmological worlds and travel and communication of shamans and spirit beings between them. As this version of the story takes us beyond the conventional ontology of our time and outside of the current frameworks of archaeologists and anthropologists for interpreting sacred artworks of Northern Eurasia, I encourage readers to adopt ‘animist eyes’ to follow along.

A Sacred Arts Tradition from the Mesolithic

At the end of the Ice Age, 11,700 years ago, the ice border of the Weichselian glaciation receded and forests increasingly took over the newly exposed taiga landscape of the Northeast European Plain. This region became the home in the early Mesolithic to new Proto-Uralic/Finno-Ugric regional archaeological cultures.

With the appearance of forests, there was a gradual replacement of the animals of the tundra, dominated by reindeer, with the those of the taiga, dominated by elk.

The foragers were compelled to innovate to survive in the unfamiliar and dangerous wilderness environment. Honko explains that “By its very nature a hunting and fishing culture had to be flexible, inventive and adaptable, for it was all that existed—and so frailly—between man’s (sic) survival and the forces of nature”.

In addition to changing their principal hunting weapons, the foragers also innovated in their sacred art, going beyond the practices that prevailed during the previous Palaeolithic Age. In the earlier time, artworks in general closely represented their subjects in appearance, like the carved waterbird figure from Siberia pictured below. In Part 2 I called this earlier representative art tradition ‘middle world naturalism’.

|

| Bird sculpture of the Siberian Upper Paleolithic Mal'ta-Buret' archaeological culture |

According to German archaeologist Thomas Terberger, the period was “an era of great climate change, when early forests were spreading across a warmer late glacial to postglacial Eurasia. The landscape changed, and the art—figurative designs and naturalistic animals painted in caves and carved in rock—did, too, perhaps as a way to help people come to grips with the challenging environments they encountered”.

Heralding the

change in art to which Terberger is referring was the Shigir Idol, that I

described in Part 2.

In the Palaeolithic Age,

a limited number of artworks in the area of Western Europe, mainly cave

paintings, had also displayed complex symbolism and fantastic ‘imaginary’

animals.

Together with the Shigir culture of the Middle Urals, they formed what was an emerging community of cultures of the forest zone of Northeastern Europe that has been called the Kunda-Butovo Cultural Unity, that I will argue in Part 4 was the initial basis of the Uralic-Finnic shamanic complex.

I called the new sacred art tradition three worlds naturalism and In Part 2 I briefly outlined what I see as its nature. I argued that the carved figures of the Shigir Idol were not only encoded representations of mythology, but also were active cultural agents, assisting the foragers to establish and mediate communication with the other world as part of appropriate shamanic ceremonies.

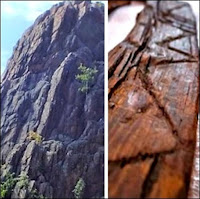

Animist Processes

Like artworks of the earlier tradition of middle world naturalism, the mythic subjects of artworks of three worlds naturalism were ‘reified’ as persons in the material world, but unlike them, they were also reified in the act of participating in animist processes such as crossing boundaries between the worlds. For example, pictured below are what may be mythic snakes, appearing as carved zig zag designs, that were reified in the process of entering from the other world through the portal of the Blue Stone cliff and winding around the Shigir Idol.

Artworks with ‘persons in process’ possessed dynamic new powers, surpassing those of artworks of the earlier tradition. For example, I argued in Part 2 that the combined and concentrated powers of the persons in process of the Shigir Idol, together with site-specific environmental elements, formed a sacred arts ‘engine’ that helped Shigir foragers to achieve an effect of immense scale: the cyclic renewal of what Ingold calls the complex network of reciprocal interdependence that underlays the existence of all beings, that I call the animist lifeworld. I suggest that such a demonstrated effect would have provided a strong incentive for the other archaeological cultures of the time to adopt the new tradition for themselves.

The tradition that I have identified gave considerable freedom to sacred artists and their rhizomic meshworks in the Mesolithic and later Neolithic Ages to vary the design of artworks in novel ways to intervene in new and critical moments in the circulation of vital or soul force. While the resulting artworks were consistent with one another in an ontological sense—i.e., all incorporated animist processes of the three worlds—they were highly individual in their appearance, each departing significantly from representational look and style.

Above are some examples of artworks in this tradition from the Mesolithic cultures of the Kunda-Butovo Cultural Unity, including from left to right, Veretye, Kunda, Onega, and Butovo at the bottom. I will explore these and other such artworks in Part 5.

I believe it is because of their individuality the artworks have to this point been treated as isolated and unconnected, not belonging to a coherent sacred art canon with its own patterns and regularities. I suggest that to see the commonality of these and other artworks rendered in three worlds naturalism requires that we adopt ‘animist eyes’—i.e., that are open to the three worlds and its processes—a practice that is largely outside the scope of mainstream archaeology and anthropology, but one that I am attempting to engage in here.

The influence of the sacred art tradition of three worlds naturalism continued into the Neolithic Era. Below is a preview of some of the examples of the Neolithic artworks of Finland and Karelia that I consider as having received this influence.

I will later identify and explore each of the artworks pictured above in Part 6, and more as well, highlighting the influences on them from the south and east and exploring what they tell us about ‘the great shadow tradition’. For now, I will review and expand my account of the nature of the new sacred art tradition of the Middle Urals, beginning with the role of mythology in the carvings on the Shigir Idol.

Mythical Consciousness

Russian archaeologist Svetlana Savchenko holds that "The dating of Big Shigir Idol to the Early Mesolithic has demonstrated that already at the turn of the Pleistocene and Holocene, people living in the Urals had developed a new system of mythological representations". (10) In her view, the sculpture, with its carved zig zag designs and figures with faces and exposed ribs may depict an ancient myth of creation.

|

| Svetlana Savchenko, beside the remnant of the paleo-lake next to which the Shigir Idol stood |

In a similar way, I argued in Part 2 that the carved figures from the Shigir Idol—two of which I have interpreted as the ‘Primordial Shaman’ and ‘the snake from the other world winding around the world tree’—may be related to the ancient creation myth, the Blue Stone of the Creation.

‘Mythology’ carries a connotation of unreality and,

as Devlet observes, is generally perceived today as “folklore, epos and fairy

tales”.

According to Siikala, “an animistic way of thinking has been regarded as typical of shamanic cultures”. She says that this way of thinking did not function on the basis of logically linked, abstract concepts. Instead, it did so through ‘mythic images’, “illustrations” in the form of “sensory stimuli”—through which phenomena and the interconnections between them were “perceived” or “seen”. This direct perception, unmediated by abstract concepts, is termed ‘mythical consciousness’, and is at the heart of the animistic way of thinking. (12)

For example, pictured above is the reified mythic image of the World Tree, that began as a sacred larch tree in the forest from which a plank was hewed, that formed the basis of the Shigir Idol. Among its many significances, the mythic image of a gigantic verdant tree at the centre of, and supporting, the animist lifeworld, made it possible for foragers to perceive the sacred unity of the three realms through which it passed and the ongoing regeneration of the animist lifeworld that it made possible.

Incommensurate Ways of Knowing

Jurgen Kremer, drawing upon the work of Barfield, outlines the nature of shamanic mythical consciousness. In it, thinking occurs through images rather than abstract concepts. It is a synthetic type of consciousness with highly permeable boundaries between ‘self’ and the phenomena—beings, places, entities— encountered by foragers, many of whom manifest as persons and some of whom inhabit other worlds. (27) It is a way of knowing that I suggest is congruent with the nature of the animist lifeworld.

Shamanic mythical consciousness stands in contrast

with the dominant way of knowing of the present day, that Siikala calls “the

rational consciousness of everyday ‘reality’”.

Today we cannot easily perceive by means of our default mode of consciousness the nature of the animist lifeworld. The two ways of knowing are nearly incommensurate, i.e., have few elements in common, making translation between them difficult. To help bridge between them, I attempted in Part 2 to present an image-rich description similar to what a shaman might have used to describe a Shigir ceremony dedicated to the regeneration of the animist lifeworld, that could have been held near their site in the Ural Mountains in 9,600 B.C.

|

| The Shigir paleo-lake |

For example, I wrote, “The female ancestral shaman at the base of the sculpture, at the boundary of the lower world, generates the life force of the World Tree. The sculpture transforms into the tree, and watered by the sacred lake, grows from the lower world through the middle world to the heights of the upper world”.

Another approach I am taking to translation between

the two ways of knowing is through using concepts drawn from the ‘new animism’

trend in anthropology, such as ‘other than human persons’ and ‘perspectivism’,

and some of my own invention or adaptation, such as ‘reification’, ‘moments’

and ‘three worlds naturalism’.

Resolving Problems

I have suggested that for Uralic-Finnic shamanist peoples, it was through mythic images, and their combination as part of extended narrative myths, that the fundamental, ontological, nature of the animist lifeworld was known. At the same time, in the view of the great French prehistorian Jean Clottes, shamanic mythology also functioned as a means for hunter-gatherer-fishers to act upon that lifeworld for survival and well-being.

|

| Jean Clottes |

In a conception that is similar to my own, Clottes argues that a primary support of foragers for acting on the animist lifeworld was with the assistance of subjects of mythic images who were “materialised” in sacred art (my own term is ‘reified’). Speaking specifically of rock paintings, he says the materialisation of a spirit being as a painted image was considered by foragers to be an ‘emanation’ of that being and for this reason was powerful. Clottes argues the painted image “retains an affinity—and sometimes even a complete identity” with the subject, the spirit guardian, making it possible for foragers to “communicate, exercise control over, and receive help” from her.

Breathing Life into Narrative Myths

Clottes suggests that artworks that materialised

the subjects of mythic images “breathed life” into, or animated, narrative

myths with which they were associated, giving them their own independent

powers.

The two arrows have the sculptural heads of waterfowl on their tips who are posed in an ‘in-flight’ position, both rendered in middle world naturalism. One arrow tip at the top above, and right, is thought to resemble a duck and the other sculpted tip to resemble a loon. Arrow tips sculpted as waterbirds are rare in the Urals, with only one other example identified there.

The waterfowl was given special status among bird

species because, in Chairkina’s words, “it, like no other, can exist in three

worlds - dives into the lower one, returns to the middle one, flies away to the

upper and returns again”.

The waterbird was associated

with powerful myths of creation.

Savchenko et al. relate the sculpted design of the Shigir arrows to the

“Ugric cosmogonic myth about a diving waterfowl who created dry land from silt

raised from the bottom of the primordial ocean”. V.V. Napolskikh, a

foremost expert on this cosmogonic myth, dates this myth to the Palaeolithic

Age.

|

| Photo from dailymail.co.uk: How did people live in the Mesolithic period? |

The tips of the

Shigir arrowhead show distinct traces of being used as projectile weapons, but

the wear on them is so slight that it is likely they were used for only a short

time, perhaps only once. Savchenko et al.

suggest that their use might have been part of “spring-autumn calendar

festivals, aimed at the reproduction of animals and birds”.

We can imagine that as part of a ritual at a spring or fall festival, the waterbird guardian—materialised as part of a sculpted arrow—would have requested a member of the local flock to surrender her life. Receiving assent, the arrow person would have acted as the instrument of the shaman-hunter to kill the waterbird, after which the bird would have been ritually consumed and her soul released to be reincarnated.

This ceremony would have helped renew

the cycle of seasonal replenishment of the flocks of waterbirds upon which the

subsistence of the foragers depended.

Recall Ingold’s statement, “In the animic ontology, the killing and

eating of game is far more than mere provisioning; it is world-renewing.”

Mythologists

Sacred artists and their meshworks were

‘mythologists’, whose artworks materialised, or reified, the subjects of mythic

images as sacred artworks. They did so through physical mediums—that I am

particularly focussing on here—such as the carved wooden figures of the Shigir

Idol and the bone sculptures of Shigir arrows.

As well, they reified the subjects of mythic images as part of sacred

art performances. These could be in the

form of the performance of the words of a story or of an incantation, the

choreography of a dance, the vocalisations of a chant, and more.

An example of a performance as a reified subject of

a mythic image is the shaman dance of the Ugric Khanty people of the Urals,

pictured below, who are considered to have continued traditions originating as

early as the Shigirs in the Mesolithic.

Comments by Koksharov suggest that subjects of

mythic images—specifically, human, animal and bird ancestors—were materialised,

or reified, in their dances. He says the

dances were “built strictly on the rhythm of the movements of the respective

creatures and have a distinctly programmatic character for the dancer, giving

him a formula for the character and sequence of movements sustained in a certain

manner”.

Two traditions

The accounts of Clottes and myself are compatible

regarding the process of ‘materialisation’, or ‘reification’, of the subjects

of mythic images in physical forms of sacred art. However, I have taken this approach further

here, identifying two distinct sacred art traditions based on this process and

investigating their presence in a specific geographical area, that of the Middle

Urals.

One of these traditions was inherited from the

Palaeolithic Age, that I have referred to as middle world naturalism. The other is what Savchenko calls “a new

system of mythological representations” based on “complex fantastic images”,

that I call three worlds naturalism. I

have suggested that it emerged in the early Mesolithic with the Shigir Idol

environmental artwork.

I believe we cannot interpret the sacred artworks of the Uralic-Finnic shamanic institutions, including those of Finland and Karelia, without taking the influence of this second tradition into account.

In Parts 4 and 5 I will follow the movement of this

tradition westward from the Middle Urals across the Northeastern Europe forest

zone to those two areas. In preparation,

in the current post I will now review and expand my consideration of both

traditions, beginning with that of middle world naturalism.

Middle World Naturalism

An example of a sacred

artwork rendered in middle world naturalism is the elk headed staff pictured

below is from the Yuzhniy Oleni Ostrov Mesolithic cemetery on an island in

Lake Onega in Karelia. The creation of

this artwork can be described in two ways.

In the artistic movement of naturalism with which we are familiar today, we can say that a human artist, as a neo-Cartesian subject, fashions from a material, e.g., bone, an object of art that takes on the likeness of another object, i.e., a living elk. Upon the viewing of it, it is seen as a naturalistic, or realistic, representation of the elk.

As an illustration of the contrasting nature of the artistic tradition of middle world naturalism, consider the way in which the foragers in Karelia might have regarded the non-material being who helped replenish of the elk herd of the area where they hunted. I suggest the shamanist foragers would have perceived this being through the mythic image of ‘spirit guardian of the elk’, an image that was well developed in Uralic myths, particularly the mythic Cosmic Elk.

With

the sacred artist and her meshwork acting as ‘midwives’, this local spirit

guardian would have been persuaded to take on the appearance of a living elk in

being reified as a shaman’s staff. When

foragers subsequently viewed the completed staff through ‘animist eyes’, they

would have seen not only the resemblance to a living elk, as one does in

neo-Cartesian naturalism, but also the personhood of the staff as a

manifestation of the mythic image of the elk spirit guardian. The staff would not have been perceived by

them as an ‘object’, ‘symbol’ or ‘representation’, but rather for what she was,

a living presence who was ready to assist the foragers.

Karjalainen refers

to the living presence of spirit persons in ritual sculptures in his study of

the Finno-Ugric Khanty culture of the Urals of the early part of the 20th

century. The sculptures he studied,

pictured below, continue sacred art

traditions reaching back to the Idol of the Mesolithic Shigir culture in

the form of their faces and in their

exposed ribs.

Karjalainen says that in

the view of the Khanty, “The (sculptural) images are not monuments, nor are

they merely dwellings for the spirit, just as the body is not only the covering

of the soul according to the Ugric view, but they are the spirit itself. That body made of

wood or metal and the spirit enclosed in it, the ‘soul’, together form a common

whole in which wood or metal are spirit and no longer mere matter.”

Shaman as ‘Midwife’

A specific instance of the role of ‘midwives’ in

the birth of sacred art comes involves the Evenki people of Siberia, from whose

Tungus language the word ‘shaman’ originates and whose worldview, according to

Siikala, shows “astonishing similarities to that of Baltic-Finnish

peoples”.

|

| Tungus (Evenki) female shaman |

Shirokogoroff says of the practice of ‘placing’, “the Tungus have occasion to manifest it, for instance, in carved wooden placings for spirits representing different animals.”

|

| Tungus carved wooden placings |

He continues, “I was impressed by the fact that

with a few cuts made in a few minutes on a piece of wood, the Tungus arrive at

representing not only the kind of animal needed, but they supply it with

certain expression: movement, rigidity, anger, smile, etc”.

Shirokogoroff chose the term “placing” because “The Tungus

idea of spirit is that the latter possesses such properties that it may be

located, embodied in a certain physical body”.

Asked for the reason for the practice of placing, an Evenki interviewed

by the author said, “If you invite somebody, would you not show your guest the

place where he might sit?”.

Here the informant demonstrates translation between

two otherwise incommensurate ways of knowing.

That is, he adopted an ‘adjusted style of communication’, pivoting from

his own animistic/mythic way of knowing to that of the neo-Cartesian way of his

interviewer, phrasing his answer in terms that were familiar and easily

understood by him. He indicates the personhood of the spirit (he is “somebody”,

a “guest”), the peer-to-peer nature of social relations with spirits (they

“invite” him), and the capacity of the manifestation of a spirit being to

inhabit a physical body (showing the guest “the place where he might sit”).

Determinations

As part of the role of the sacred artist and her

meshwork as midwives to the birth of a sacred artwork, they endowed the artwork

with the attributes that made it possible for spirit beings to manifest as

beings in the material world, in addition to their existence in the other

world. I call these attributes ‘determinations’, a concept I have borrowed from

the dialectical logic of Hegel that refers to the attributes that establish, or

determine, the existence of an object.

In the case of the elk headed staff, the design determinations include a body constructed of elk antler and designs that captured the appearance of an elk in the middle world, including the characteristic shapes of the muzzle, ears, eyes, nose and prominent lips. When these design determinations were in place, the artwork was ready to host the non-material determination—the living presence of the elk spirit guardian—who animated the sacred artwork and readied it to intervene in what I call a ‘moment’ in the circulation of vital or soul force.

Karjalainen describes the

creation of a Khanty sacred sculpture in a similar way, using the Khanty term ‘tonx’, as meaning both ‘spirit guardian’ and

‘idol’. He says, "After a piece of

wood has been given a shape of a human or after a tin cast, having a certain

human form, has hardened, it is important to transfer or to indwell in it a ‘tonx’ of the spirit which the figurine depicts,

and only after that the image becomes a ‘tonx’ to which necessary honours can

be given".

Moments

I referred to the capacity of a sacred artwork to

intervene in a ‘moment’ in the circulation of vital or soul force. I will now briefly review the concept of

moments. In my presentation on the topic

in Part 2, I pointed out that Ingold describes the animist lifeworld,

what he calls the “complex network of reciprocal interdependence”, as a

totality comprised of spirit persons, humans, animals, plants, insects, and all

other forms of life who are “borne along in the current” of what he calls vital

or soul force as it circulates freely throughout the three worlds.

I introduced the Hegelian term moments to refer to the points of intervention that were especially critical for maintaining the flow of vital or soul force in the animist lifeworld. A moment that we have just encountered is the negotiation of foragers with spirit guardians for a replenished game herd through the ritual of animal ceremonialism. Shamans frequently called upon sacred artworks such as the animal headed staffs to assist them in conducting these ceremonies through attracting guardian spirits of elk and mediating dialogue with them.

In the new wilderness environment of the early Mesolithic, the moment of replenishing the supply of game for a local area, such as elk or waterbirds, remained a primary one for foragers. However, they were also encountering new moments that were more complex and demanding than this, requiring artwork persons with powers beyond those conferred through middle world naturalism. This recalls Terberger’s view stated above that that in the Mesolithic, art had changed “perhaps as a way to help people come to grips with the challenging environments they encountered”.

In

Part 2 we saw a moment that was extraordinary in its scope and

urgency: the cyclic renewal of the

animist lifeworld. This was accomplished

with the assistance of the Shigir Idol environmental artwork, that exercised

powers of a new, unprecedented order.

Three worlds naturalism

I argued that to create artworks with enhanced

powers, the sacred artists and their rhizomic meshworks addressed a more

fundamental level of animist reality than was possible through the earlier

tradition of middle world naturalism. That is, while reifying spirit persons in

the artworks, they also reified their acts of participation in one or more of

the animist processes that I explored in Part 2, including

transformation of form; merging of beings; losing and gaining of vital force;

and travelling and communicating across the three worlds. I used the term

‘persons in process’ to refer to the new sacred artwork beings who were

created. I chose the name ‘three worlds

naturalism’ for the new tradition because it was based on the incorporation of

design determinations that encompass the three worlds, not just the middle

world.

The reification of the

act of engagement in an animist process was made possible through a particular

type of determination, that we can call a ‘process determination’, which was

not present in middle world naturalism.

It captured the subject of the artwork in the midst of engaging in an

animist process. We can take as an

example the female Shigir lineage shaman figure on the Shigir Idol.

While one design determination links the shaman figure to the middle world—i.e., she resembles the female shaman at the left in terms of basic body form—she also displays three design-related determinations that link her to processes encompassing the three worlds. They include, first, her exposed ribs that show shamanic death and rebirth, linking her to the process of drawing upon and surrendering of vital force or soul force. The second design determination consists of the dots between her legs that have her birthing of the power of the World Tree, connecting her to the process of the free circulation of vital or soul force. The third design determination is her two-plane face, showing her—the spirit of a deceased shaman—as an ancestral shaman spirit person, linking her to the process of transformation of being.

These determinations constituted a triple empowerment for the female shaman figure of the Shigir Idol. Additionally, she was empowered by her position at the rear and bottom of the Idol, that in mythic terms placed her at the base of the World Tree, in direct contact with the Blue Stone gateway to the other world. In this location she was able to assume the position of mediator between the worlds.

The works of three worlds naturalism characteristically incorporate a recognisable middle world form, for example, the body shape of the female ancestral shaman figure of the Shigir Idol, and for this reason cannot be called fully non-representational. In this sense, the initial point of departure of the new tradition can be said to be from the older one of middle world naturalism. However, the new tradition gave sacred artists and their meshworks broad warrant to go beyond the constraints of the older tradition, to flexibly tailor and adapt determinations of form and design of the artworks in novel ways to address specific critical moments in the flow of vital or soul force. The resulting departures from middle world appearance of the artworks causes contemporary interpreters to use terms such as ‘fantastic’, ‘abstract’, ‘stylized’, ‘symbolic’ or ‘schematic’ to describe them. For example, Savchenko uses the term “fantastic image” to refer to the female ancestral shaman figure.

The term ‘fantastic’ encourages the tendency to see the artworks as irregular or idiosyncratic, and not part of a new sacred arts tradition. An interpretive schema is needed that ‘normalises’ their design in terms of the tradition of three worlds naturalism. In this spirit, I offer the following seven characteristics of artworks rendered in the new tradition that can be applied as criteria in their interpretation:

Savchenko says

“representations of the (Shigir) tribe's worldview found expression not only in

monumental sculpture, but also in a smaller sculpture….”

|

| View an animation of the staff head Here |

Savchenko says “A staff head is an object which had a special status”. With the insertion of a wooden rod in the hole carved in it, it became an active companion and assistant of the shaman in rituals. Based on the evidence of other shaman staffs in northern Eurasia, it is likely the pole or stave inserted in the head would itself have been considered a reification of the World Tree.

The shaman’s staff head is dated to the early Mesolithic, 9197

BC, contemporary with the Shigir Idol. For Savchenko, it combines the features

of several creatures into a single, new one. The image is “grinning, growling,

menacing”.

Savchenko views the wide swollen visible nostrils, shaped as shallow indentations, elongated muzzle and a bared mouth as suggesting the faces of a wolf and a bear. Both were prominent in the mythology of the Uralic area. The bear was seen as the powerful King of the Forest, with an intelligence and personhood equal or superior to that of humans. The wolf, with its fearsome powers of hunting and defending, was in later Finnish mythology a guardian of the gates of Tuonela, the northern abode of the dead. The wolf’s protector goddess was Louhi, who presided over Tuonela and whose name is associated with the expression langeta loveen, i.e., fall into shamanic trance.

The side view below shows a long jaw with rows of

teeth and the eyes like the staff head.

Savchenko says it suggests the mammoth pike of mythology.

Interpreting the Shaman Staff Head

What

is the critical moment in which the Shigir staff head was designed to

intervene, within the totality of moments comprising the circuit of vital or

soul force in the animist network of reciprocal interdependence? Based on the views of Savchenko, it may have

been related to the moment of predation.

The makeup of the rhizomic meshwork that created

the staff head person might have included the artist/carver, the spirit

guardians of the three predator species, the guardians of the species who were

the objects of predation, the elk spirit person whose antler was being carved,

and the tree spirit guardian who contributed wood for the rod.

Acting with the meshwork, the sacred artist would have produced physical determinations including the carved antler material and the crafted wooden rod, as well as a series of ‘process’ design determinations that merged the middle world appearances of the three predator species into a single new animist being. The design determinations enabled the animist process of transformation, specifically that of merging beings and that of concentrating their three individual vital or soul forces into one.

For

Savchenko, the design determinations of this merged being suggests a ‘fantastic

beast’.

The Staff Head as Part of a Ritual

When the carving of the staff head was complete, the meshwork and the forager band, as part of a ritual, would have formally recognised the personhood of the staff head and conferred upon it the agency to help address the critical moment of predation in the circulation of vital or soul force.

We can imagine the nature of such a ritual, perhaps conducted at the sanctuary where the Shigir Idol stood. It is what I would call a portal to the other world, existing in the liminal space of the sacred cliff and the shoreline of the Shigir paleo-lake.

The ritual might have begun with the shaman

entering a journey state through drumming and chanting and then adjusting their

style of communication to ask for the assistance of the shaman staff person.

Receiving agreement, the shaman would have waved the staff aloft, summoning the

three predator species guardians—wolf, bear and pike—as well as those of the

hunted species of elk and fish. The shaman’s

staff would have generated a ‘zone of sociality’ in which social relations

between human persons and the spirit persons could be carried on.

Through

the mediation of the shaman and the staff head person, the participants, who

had also adopted adjusted styles of communication, might have negotiated new

terms of the hunt and the relative share to be either surrendered or gained by

each. In this way, I suggest, the

composite staff head person would have demonstrated its powers to assist the

shaman to intervene in the moment of predation, a complex moment that could not

have been addressed through an artwork rendered in middle world naturalism. That is, in the older tradition, a member of only

single species could have been reified, and would have possessed a relatively

limited, focussed range of powers for ritual activity.

Negotiating

the relative share of elk and fish to be taken by predators was a critical

moment for humans in the circulation of vital or soul force, but it was clearly

also critical for the other parties to the negotiation. In addition to a human’s share of vital force

for subsistence, there was a predator’s subsistence share, and on the part of

the hunted species such as the elk, a share of soul force of the herd that

would be surrendered by the elk guardian spirit. This is a graphic example of

the reciprocal interdependence of humans and those species as part of the

animist network. Recall Ingold’s view that in the animic network, beings depend

for life on constantly drawing on the “vital or soul force” of other beings

and, on the other hand, surrendering it to them.

It is conceivable that any one of these parties, not just the human sacred artist, could have originally initiated the process of creation of the staff head person to assist in resolving the issue of relative shares of game. I suggest that the existence of the Shigir shaman’s staff person can be seen as material evidence of cross-species, trans-worlds communication and negotiation that took place in the forests of the Middle Urals of the Mesolithic. If this was the case, it expands our picture of the complex interdependent animist network, building upon and filling out the basic principles of it as provided by Ingold.

Mythic Images Across Time

Across centuries and millenniums, a primary mode of

existence and sharing of shamanic mythology among peoples of the Northeast European subarctic forest belt

was as sacred art—stories, songs, dances, carvings, rock paintings, and

more—that reified or materialised the beings, places, and processes that were

the subjects of mythic images.

|

| Samoyed shaman drumming by the fire. (O. Finsch 1894) |

Mythology represented a repository of these reified subjects, with their distinctive powers. The contents of this repository were shared widely among Uralic archaeological cultures as part of cultural community in the Mesolithic era and a contact network in the following Neolithic Comb Ceramic period.

The ‘process

determinations’ of subjects of

mythic images were elements of the repository.

They were available to be incorporated in sacred artworks of other

cultures sharing similar ontological frames, and to be animated anew to help create

powerful sacred art allies.

Recall the design

determination of the female shaman person on the Shigir Idol, above, consisting

of the dots between her legs that show her birthing of the power of the World Tree. According to Chairkina, this represents the possible

incorporation of a design determination from an earlier Palaeolithic female

rock painting person. The red ochre

painting, below at left, is from Ignatievskaya Cave in the South Urals,

dating to the late Palaeolithic, at least a thousand years older than the

female ancestral shaman of the Shigir Idol.

Panina says of this example, “it is possible to

trace how the tradition of depicting a character-symbol, which is significant

for ancient people, is preserved between such ancient eras as the Upper

Paleolithic and Mesolithic".

The Power of a Process

Determination

What is the basis of the

power of a process determination? Hegel,

analysing an object in terms of dialectical logic, states that it is the

concentration of many determinations, and that the determinations

“interpenetrate each other reciprocally”.

Applying this logic to an animist entity—a sacred artwork—we can say

that the presence of a spirit guardian as a determination of an artwork

penetrates all other determinations of the work, including the creative design

features, investing them with the power and presence of that spirit person.

I believe that a similar

conclusion is implicit in Karjalinen’s observation about the ontological nature

of Khanty sculptures that we encountered above.

He said that “the body made of wood or metal and the spirit enclosed in

it, the ‘soul’, together form a common whole in which wood or metal are spirit

and no longer mere matter”.

Design Determination as Marker

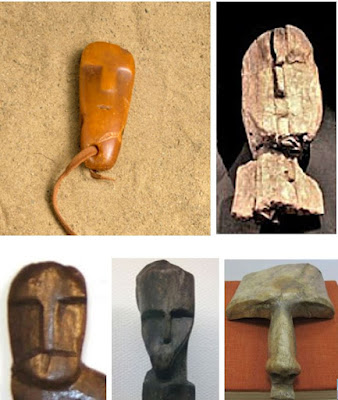

The main four ‘process’ design determinations of the Shigir Idol are pictured below.

The determinations include the larch wood plank as World Tree, the exposed ribs of the ancestral shamans, the faces of the ancestral shamans, and the snakes entering from the other world. We will see in coming posts that they all were incorporated in later artworks of other cultures and times. I will concentrate for now on a single example from the Shigir Idol, the ancestral shaman’s face design determination.

The faces on the Shigir Idol are structured on two

planes, with a prominent forehead and narrow strip of the nose as one plane,

and the deepened surface of the cheeks and mouth as the other. Chairkina refers

to this as the “Urals style”, that is “conceptually uniform, ‘constructed’ as a

whole from several repeating elements”.

While the faces are uniform in this way, at the same time they display unique aspects characteristic of specific human faces, suggesting separate mythical subjects. Devlet considers that they may have been actual lineage shamans of the Shigirs: “The seven vertically aligned anthropomorphic figures on the Shigir Idol conceptually conform with the notion of shaman clans, inherited shamanic gift and shamans-ancestors who give their successor special powers.”

I suggest that the process design determination of

the two-plane face acted as a uniform ‘container’ for the various unique

personas of the clan shaman spirit persons reified on the Shigir Idol. It transitioned them to the status of

‘persons in process’ with the “special powers” that as mythical lineage shaman

ancestors they in turn collectively conveyed to the topmost figure of the idol,

the Primordial Shaman.

The facial design determination went on to be

repeated as part of later artworks across Uralic cultures, suggesting the

determination had become available as part of the mythological repository. Savchenko says, “The transmission of the

tradition of the anthropomorphic cult image of the cheeks and eyes in a single

plane, that was fixed among the characters of the Shigir idol,

subsequently spread in the forest zone from Northern Europe to Siberia”.

I suggest that the “Urals style” of facial appearance as a design determination—with its power as a sacred art ‘container’ through which a spirit person was able to transform to a mythical ‘person in process’—proved valuable to sacred artists and their meshworks for their own artworks in addressing a host of critical moments in the circulation of vital or soul force. This uptake was across a span of several thousand years, encompassing various archaeological cultures. By the Neolithic Age, the tradition had become established across the area from the Urals to Finland and Karelia, as the examples of artworks below show.

The examples include ones from Karelia, then Finland on the top row, and ones from Estonia, Lithuania, and the Volga-Oka area of Russia on the bottom row.

I would argue that as a process determination, the Shigir

facial design determination became a marker of the geographical spread

of the tradition of three worlds naturalism from which it arose. Wherever it appeared, the local sacred

artists there were already practitioners of the new sacred art tradition. That

is, by incorporating the ‘fantastic’ design determination the Shigir ‘Ural

style’ face, the artist and her rhizomic meshwork had already departed from the

canon of middle world naturalism. Moreover, the facial design determination only

achieved meaning through establishing the subject of an artwork as a person in

process, the hallmark of the tradition of three worlds naturalism.

Looking Ahead

In the present post, Part 3, I have explored

what I consider to be a new sacred art tradition that began in the Middle Urals

in the early Mesolithic, that I call ‘three worlds naturalism’. I suggest that the initial spread of three

worlds naturalism from the Urals was during the early Mesolithic Era.

For example, below at left is ritual mask of the Mesolithic

Veretye archaeological culture, located in northwest Russia, east of Lake Onega. It appears to incorporate the “Urals style”

facial process determination of the Primordial Shaman of the Shigir Idol, at

right, a marker for the presence of the tradition of three worlds naturalism in

that area.

The Veretye culture was a part of the Kunda-Butovo Cultural Unity, a community of archaeological cultures arrayed across the Northeastern Europe forest during the Mesolithic. In Part 4 I will suggest that the Uralic-Finnic shamanic institution initially developed on the basis of this community. In Part 5 I will argue that the sacred arts tradition of three worlds naturalism was a core component of this institution and will explore artworks rendered in the new tradition from cultures that were part of it, particularly those of Finland and Karelia.

Sources

1. Siikala, Anna-Leena. Mythic Images and

Shamanism: A Perspective on Kalevala Poetry. Helsinki : Academia

Scientiarum Fennica, 2002.

2. Clottes, Jean. What

Is Paleolithic Art? Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity. Chicago

and London : University of Chicago Press, 2016.

3. Honko, Lauri; Timonen,

Senni; Branch, Michael. The Great Bear: A Thematic Anthology of Oral

Poetry in the Finno-Ugrian Languages. Oxford UK : Oxford University

Press, 1994.

4. Savchenko, Svetlana.

Early Mesolithic bone projectile points of the Urals. [ed.] Harald Lübke, John

Meadows and Detlef Jantzen Daniel Groß. Working at the Sharp End: From Bone

and Antler to Early Mesolithic Life in Northern. Europe. Kiel and

Hamburg : Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie., 2019.

5. Lidz, Franz. How the

World’s Oldest Wooden Sculpture Is Reshaping Prehistory. New York Times. [Online]

March 22, 2021. [Cited: March 22, 2021.] https://www.nytimes.com/.

6. Zhilin, Mikhail,

Savchenko, Svetlana, Hansen, Svend, Heussner, Karl-Uwe and Terberger, Thomas Early art in the Urals: new research

on the wooden sculpture from Shigir. s. 362, s.l. : Cambridge

University Press, April 2018, Antiquity, Vol. 92, pp. 334-350.

7. Palacio-Perez, Eduardo

and Redondo, Aitor Ruiz. Imaginary Creatures in Palaeolithic Art:

Prehistoric Dreams or Prehistorian's Dreams. s.l. : Antiquity

Publications Ltd., 2014, Antiquity, Vol. 88, pp. 259-266.

8. Comba, Enrico Mixed

Human-Animal Representations in Palaeolithic Art: An Anthropological

Perspective.. [ed.] Jean Clottes. Tarascon-sur-Ariege : Actes

of IFRAO Congress, September 2010 – Pleistocene art of the world; Symposium:

Signs, symbols, myth, ideology, September 2012.

9. Curry, Andrew. This

11,000-year-old statue unearthed in Siberia may reveal ancient views of taboos

and demons. Science. [Online] April 25, 2018. [Cited: September 4,

2020.]

10. McKie, Robin.

Carved Idol from the Urals shatters views on birth of ritual art. The

Observer. May 20, 2018.

11. Savchenko, Svetlana. РАННЕМЕЗОЛИТИЧЕСКОЕ

РОГОВОЕ НАВЕРШИЕ В ВИДЕ ГОЛОВЫ (Early Mesolithic Pommel in the Form of a

Fantastic Beast From the Middle Trans-Urals). 2018, Problemy istorii, fi

lologii, kul’tury, Vol. 2.

12. Devlet, E.G.; Devlet,

M.A. Myths in Stone: World of Rock Art in Russia. Moscow :

Aletheia, 2005.

13. Siikala, Anna Leena.

Shamanic Knowledge and Mythical Images. [book auth.] Anna Leena Siikala and

Mihaly Hoppal. Studies on Shamanism. Helsinki and Budapest : Finnish

Anthropological Socieity, 1998.

14. Savchenko S.N., Yurin

V.I., Zhilin M.G. Flying arrow - flying bird (bone arrowheads with

sculptures on the edge) (Летящая стрела – летящая птица (костяные наконечники

стрел со скульптурами изображением на острие). 10, 2015, Tver

Archaeological Collection (Tверском археологическом сборнике), Vol. 1.

15. N.M, Chairkina. Anthropo-

and zoomorphic images of the Eneolithic complexes of the Middle Trans-Urals

(АНТРОПО- И ЗООМОРФНЫЕ ОБРАЗЫ ЭНЕОЛИТИЧЕСКИХ КОМПЛЕКСОВ СРЕДНЕГО ЗАУРАЛЬЯ). 23,

Yekaterinburg : s.n., 1998, Questions of archeology of the Urals (Вопросы

археологии Урала).

16. Napolskikh, V.V.

The Diving-Bird Myth in Northern Eurasia. [ed.] M. Hoppal and J. Pentikainen. Uralic

Mythology and Folklore. Budapest, Helsinki : Ethnographic Institute of

the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; Finnish Literature Society, 1989.

17. Ingold, Timothy.

Totemism, animism and the depiction of animals. The Perception of the

Environment. London and New York : : Routledge, 2000.

18. Zhogi, Gleb. Shigir

Idol. uralcult.ru. [Online] July 1, 2021. [Cited: September 14, 2021.]

uralcult.ru/articles/museums/i101419/.

19. Chernetsov, Valerii.

Rock Art of the Urals (Naskal'nya izobrazheniia Uralia). Moscow :

Science Publishing House, 1971.

20. Karjalainen, K.F. Die

Religion der Jugra-Volker 1-2. Helsinki: Porvoo : Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1921.

21. Siikala,

Anna-Leena. Review of Northern Religions

and Shamanism by Mihaly Hoppal, Juha Pentikainen. Anthropos. 1995, Vol.

90.

22. Shirokogoroff, S.M.

Psychomental Complex of the Tungus. London : Kegan Paul, Trench,

Trubner & Co. Ltd., 1935.

23. Chairkina, N.M. Bol

`shoy Shigirskiy Idol [The Great Shigir Idol]. 41, 2013, Ural'skiy

istoricheskiy [Urals Historical Bulletin], Vol. 4.

24. Devlet, E.G. “Transparent”

flesh: interpreting anthropomorphic figures on the Shigir idol (“Prozrachnaya”

plot`: k probleme interpretatsii anptropomorfnykh izobrazhenii). The Urals’

Historical Bulletin (Ural’skiy istoricheskiy vestnik). 2018, Vol. 1, 58,

pp. 20-28.

25. Savchenko, S.N.Early

Mesolithiic antler sculpture in the form of a head, a fantastic beast from the

Middle Urals (РАННЕМЕЗОЛИТИЧЕСКОЕ РОГОВОЕ НАВЕРШИЕ В ВИДЕ ГОЛОВЫ). 2018,

Problemy istorii, fi lologii, kul’tury (Problems of history, philology,

culture), Vol. 2, pp. 191–207.

26. Zhilin, Mikhail.

Early Mesolithic Hunting and Fishing Activities in Central Russia: A Review of

the Faunal and Artefactual Evidence from Wetland Sites. Journal of Wetland

Archaeology. 2014, Vol. 14.

27. Kremer, Jurgen, The Dark night of the scholar: Reflection on culture and ways of knowing. ReVision, Spring 1992, Vol. 14, Issue 4.

No comments:

Post a Comment